Creativity in Schools – Sir Ken Robinson

So, what has happened almost a decade on?

The first of a series of iconic TED talks about how education needs to ‘shift paradigms’ occurred almost a decade ago back in June 2006 (yes, that was ten years ago this year). Sir Ken Robinson set the ball rolling with his TED Talk about how ‘schools kill creatively’ – a talk that still tops the ‘all time viewed’ lists with 13 million views in 2012…and over 37 million views as I type this in February of 2016.

Sir Ken has his critics who say that it’s easy to be seduced by his words when there is no action plan to apply (read his books and there are plenty of sensible and useful words of wisdom as to how we can improve things….). Personally I totally agree with Ken (and in fact saw Ken give some similar insights earlier in his career when he was professor of education at Warwick University in the UK).

So, a decade on, where do we stand?

Sadly, given all the hype and constant gossip about how wonderful Sir Ken’s vision is, we (schools) seem to be achieving very little in terms of creating (no pun intended…) a genuine shift in approach to how education is responding to the needs of business and enterprise, cultural and social anthropology and a rapidly changing modern world.

We know that schools are notoriously slow on the take up of most things. Actually, that’s not quite true. They are often quick to buy in to an idea but then lack the strategy and vision (planning and money) to see it through. I remember on one of my first teacher training experiences at a school in Edmonton, North London (around 1983) seeing a white van back up to the Design department to unload fifty brand new BBC Master computers with screens. This was the age of change and technology…this would transform what we were to do. My Head of Department was grinning like a Cheshire cat…but quite quickly I discovered that not all was well. I was asked to give some INSET on their use to all teachers (two weeks in to my first teaching practice aged 19 or so…) and thereafter all but two machines ended up in a locked cupboard. I had one BBC Master to play with and one other was taken to the front of school for administration staff to play on.

And there is the rub.

Staff had no time to ‘play’ and many believed that these contraptions were the devils spawn (and to be honest many struggled with the Banda copy machine in the staff room let alone any other technology above a hole punch and stapler). Government gave high end kit to schools to help stimulate creativity and technological change without offering time and budget to allow it to happen. Things stalled and ground to a halt. I remember re-visiting the school for another training period about two years later and the BBC masters were still in the same cupboard….although a couple of Atari ST machines had entered the department now with their ‘colour GUI’ and a Meg of RAM if I remember correctly.

The desire for change

This may seem harsh but schools are not always great at adapting to change from a strategy and vision standpoint. They mean well, and those in seats of decision making will often embrace the idea of something new from a concept standpoint, but very few understand the need to support that vision with a hands on, practical and feasible plan of action. This is frequently not about money; it’s about the desire to want to change the way we do things so that they improve; to help children get prepared for a world of work that we don’t really fully understand ourselves (the frequently banded about quote ‘we are preparing kids for jobs that don’t yet exist’ springs to mind) and to fundamentally change the curriculum content and approach we have in place.

Subjects change but curriculum’s, on the whole are antiquated. Creativity is not a new thing in schools. Arguably primary and kindergarten staff have been doing ‘STEM’ and ‘STEAM’ activity in schools for decades – playing, building, failing and working in teams often in a sandpit or on the carpet with tons of Lego, Stickle bricks (remember them?) and other cool things – combining Art, Science, Design, Language, Maths…

What we need, as students move up to secondary or high school, is a rudimentary change to what is delivered at the curriculum chalk face. For this to happen we almost need to wipe the slate clean and start again.

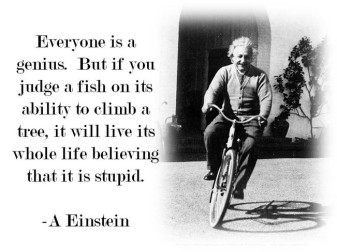

The problem we have is that many who are at the decision making end of directing and developing curriculum’s at government or school level have frequently come up through that industrial age of education that Sir Ken refers to in his original TED talk (and so expertly captured in the RSA animation of that talk RSA Sir Ken Robinsons TED Talk). These folk have been button-holed as ‘bright’ or ‘academic’ (and many are…) and have seldom been through a creative area of study at school. Rote learnt knowledge has been seen as a better foundation than one where they have had to solve complex problems on paper through an iterative process or with their hands in Art, Design and Technology – or indeed on stage through performing arts. Arguably, the nearest many have come to creative thought or play has been on the rugby or hockey pitch (or other team sport where spontaneous flair and decision making is often required).

Reverse Engineer the way we do things

To achieve the change that Sir Ken spoke about needs a fundamental upturn in philosophy where the practical application of knowledge is seen to be on an equal footing (?) with the ability to simply rote learn facts for an exam. For this to happen we need to reverse engineer the whole structure of academic acceptance.

What do I mean?

The world of work needs a workforce who are creative, flexible and can apply previously harboured knowledge well (be that from school, university or work experience). They need to be worldly, good communicators, gregarious, empathetic, skilled and confident.

Firstly, governments need to have ministers responsible for education in employ who have actually come from an educational background – folk who have delivered and managed in schools and who have a better (more realistic?) understanding of what students and teachers need to deliver.

Secondly, if a student chooses to go directly into the world of work from school, rather than attend University, that is not necessarily a bad thing. Parents and schools need to understand that in the same way that industry does. Getting hands on experience of a business may well put them in better stead than doing three years in further education with no guarantee of a job at the end of it. Accepting that is key and is normally a fight for parents who get caught up in the ‘league table’ nonsense where students often achieve artificially high grades centred on a factory process – the success of which is based on sitting a one and a half hour paper at the end of two years study. Not good. You also have the ‘when I was at school’ scenario when parents of a certain generation were educated in schools that led them to believe that some subjects were more academic than others. It’s a big rut to climb out of psychologically.

Thirdly, universities need to supply courses that are current, flexible in delivery (able to change content mid course to satisfy employment demands) and that allow students to apply what they have discovered at school rather than treating them all as ‘starting from scratch’. I have heard of universities that take students onto certain courses and simply tell them that they have to ‘unlearn’ what they did at school and do things differently; so your first year becomes, in effect, a foundation year. What a waste of schooling and finance. Schools and universities need to talk to each other more.

Schools need to de-construct and review current curriculum’s. They need to have the confidence to do it. Do we still need Latin? Do we still need to study Shakespeare (as opposed to other more contemporary writers…)? Should everyone study at least one foreign language? Do we continue to have the mainstay of ‘core’ subjects at the heart of what schools do – Maths, English and Science (with extra languages, Art, Geography, History, Design and Technology in tow)? I don’t know, but questioning and jiggling to take some risk would be healthy.

For me I’d love to have Design at the core of the curriculum with science, business, humanities, languages, maths and the arts radiating off. The idea that working with your hands (manufacture, creation, enterprise) is the realm of ‘less able’ students is totally unfounded. Bright students can, and do, work with their hands. Art has long been considered the ‘accepted’ manual skill for bright students along with Music. Sadly Drama, Dance and Design have always struggled to gain the same acceptance along with physical education (a tough A-Level in reality).

For me I’d love to have Design at the core of the curriculum with science, business, humanities, languages, maths and the arts radiating off. The idea that working with your hands (manufacture, creation, enterprise) is the realm of ‘less able’ students is totally unfounded. Bright students can, and do, work with their hands. Art has long been considered the ‘accepted’ manual skill for bright students along with Music. Sadly Drama, Dance and Design have always struggled to gain the same acceptance along with physical education (a tough A-Level in reality).

In essence, anything that has not grown out of the land or ‘popped’ out of a human has been designed; someone, somewhere, has sketched the idea and developed it. That’s both academic and creative in my book.

As Sir Ken said, we need to ‘shift paradigms’.

We need to educate and nurture future wealth creators (not just financial – anthropic wealth too) who can develop innovative products and services. I reiterate, despite Sir Kens 37 million ‘likes’ on the need to have creativity in the curriculum there are still many within government and education who feel it’s not required a decade on. The current EBACC debacle in the UK is looking to throw out creative education from the curriculum and quite rightly there is uproar from many sides across business and education.

The biggest anxiety for me, in all of this, is that we will probably still be having the same conversation in several years’ time, recognising that creativity is important, that we drastically need curriculum change and so on. But will folk have listened? Will there have been change? I truly hope so.

By that time Sir Ken’s original talk will be up past the 100 million views mark. Probably.